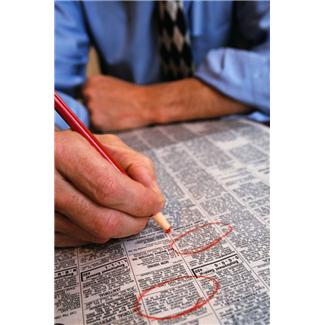

"The Law School Bubble: How Long Will it Last if Law Grads Can't Pay Bills?"

By: Steve Grumm

This ABA Journal piece is a must-read if you’re interested in how legal education is financed (i.e. the widespread availability of loans), the intersection of the lending system with a bleak job market, and what may happen from here. The news ain’t all good. Authors William Henderson and Rachel Zahorsky begin with some sobering present-day statistics…

In 2010, 85 percent of law graduates from ABA-accredited schools boasted an average debt load of $98,500, according to data collected from law schools by U.S. News & World Report. At 29 schools, that amount exceeded $120,000. In contrast, only 68 percent of those grads reported employment in positions that require a JD nine months after commencement. Less than 51 percent found employment in private law firms.

The influx of so many law school graduates—44,258 in 2010 alone, according to the ABA—into a declining job market creates serious repercussions that will reverberate for decades to come.

…

The piece then goes on to trace the historical role of federal lending (both in backing private loans and direct lending) in funneling cash into the legal education system. Henderson/Zahorsky identify a serious, looming problem for federal lending. Now that Uncle Sam is doing so much direct lending he is betting that, as a lender, he’ll make money back on future interest revenues paid by law-student/attorney borrowers. But is this realistic in light of a stagnant (and maybe in the long term, shrinking) job market?

By failing to make rigorous, realistic actuarial assumptions in deciding who to lend money to and how much to lend, the federal government avoids politically uncomfortable trade-offs. Everyone can go to college. And if you can get accepted into law school, the government will finance that, too.

But as the economist Herbert Stein once said, “If something cannot go on forever, it won’t.” The federal government’s gamble that higher education will continue to result in higher personal incomes eerily echoes Wall Street’s risky assumption that historical patterns in real estate values would carry forward forever and enable many sliced-and-diced mortgage-backed securities to attain AAA ratings.

While it may be politic, even patriotic, to assume that the higher-education-equals-higher-income equation is fact, for investors it remains, at best, aspirational. Since 2008, private investment in nearly any market has been reluctant. The capitalists aren’t taking this education-equals-high income bet; if they did, the terms they would demand would likely change the choices that student borrowers are now making.

Unless the government’s actuarial assumptions on student loan repayments turn out to be correct, federal funding of higher education is on a collision course with the federal deficit.

Optimistic assumptions of future growth and earning power, however, are completely at odds with the financial landscape that has given rise to the so-called scamblogger movement and some recent lawsuits by graduates alleging their schools committed fraud and other deceptive practices regarding portrayals of job prospects.

I wish I had more time to go into depth on this article, but for now the above must suffice as a teaser. It’s worth a full read.

Permalink Comments off